The problems with JavaScript

The main characteristics of JavaScript include encapsulation, messy code, and dynamic type system.

Dynamic type system

In a dynamic type system, the same variable can be re-used to store a reference to objects of different types or store values of different types.

/**

* An example of dynamic type.

*/

var person; // could be any type

person = "John Papa";

person.substring(1, 4);

person = 1;

person.substring(1, 4); // will cause an exception at runtime

The good:

-

Variables can hold any type of object e.g. boolean, string, number, object literal etc..

-

Types determined on the fly.

-

Implicit type coercion (ex: string to number)

'1' == 1 // will be true

The Bad:

- Difficult to ensure proper types are passed without tests.

- Not all developers use

===e.g. telling JavaScript not to coerce a type such as converting string"1"into a number1. - Enterprise-scale apps can have 1000s of lines of code to maintain.

Solution for the problem include,

- writing better JavaScript code and applying various patterns,

- writing in TypeScript,

- writing in CoffeeScript, or

- writing in Dart.

One can write in Dart or CoffeeScript and output JavaScript. But TypeScript is JavaScript (a superset of JavaScript).

All programming languages are doing the same thing, but they exist on different layers. For example, both Java and C# are one level above C and C++. C/C++ is above assembly, which is above machine code.

What is TypeScript

TypeScript is a typed superset of JavaScript that compiles to plain JavaScript. TypeScript is not a totally separate language; it's a language built on top of JavaScript, by adding new features and additional key words.

Some key TypeScript features include,

- supports standard JavaScript code,

- provides static typing so we can catch incorrect data types through tooling (e.g. red lines in editor), compilation process or after fact (e.g. unit testing),

- provides encapsulation through classes and containers i.e. modules,

- supports for constructors, variables, properties and functions,

- supports interfaces to define the mimimum members that a particular type must have,

- supports arrow functions

=>, - enables intellisense and syntax checking if using supported editor.

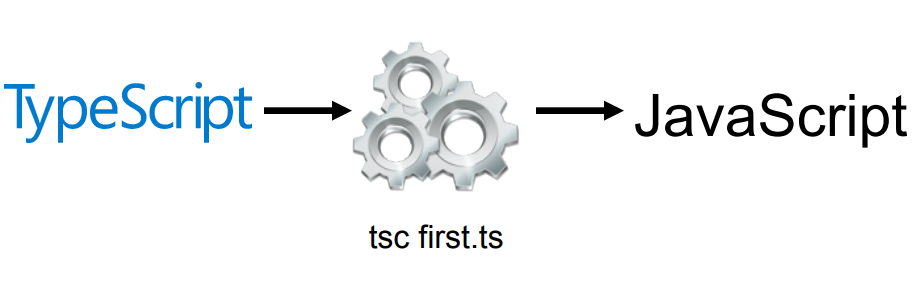

The TypeScript compiler is what converts TypeScript code into plain JavaScript code, and it works as below,

Some keywords and operators in TypeScript

| Keyword | Description |

|---|---|

| declare | Creates an ambient declaration, meaning the variable doesn't exist in the current file but exists in somewhere else such as in a referenced library |

| class | Container for members such as properties and functions |

| constructor | Provides initialisation functionality in a class |

| exports | Export a member from a module |

| extends | Extend a class or interface |

| implements | Implement an interface |

| imports | Import a module |

| interface | Defnes code contract that can be implemented by types |

| module / namespace | Naming container for classes and other code. namespace is preferred over module |

| public/private | Member visibility modifers |

| … | Rest parameter syntax |

| => | Arrow syntax used with defnitions and functions |

| < typeName> | < > characters use to cast/convert between types |

| : | Separator between variable/parameter names and types |

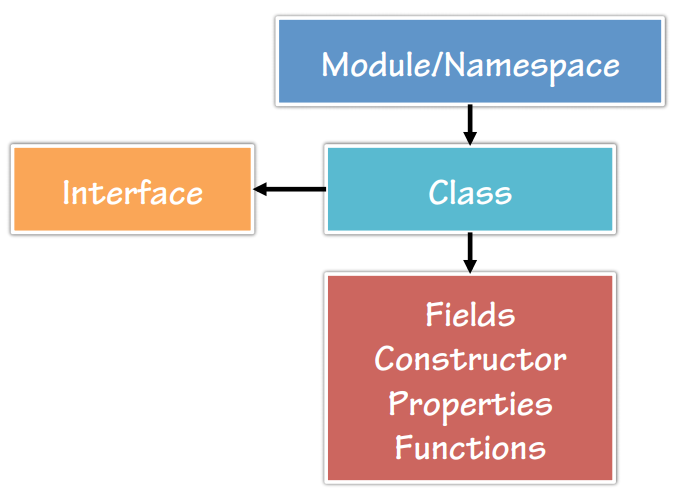

The code hierarchy in TypeScript is as following:

Tooling and framework options for TypeScript

Some of the frameworks and tolls for TypeScript are,

- Node.js (server side framework)

- Sublime, Emacs, Vi, VS (including auto compling into JavaScript upon saving a TypeScript file), VS Code, Atom, and WebStorm

Installing the TypeScript compiler on Ubuntu

# Install the command-line TypeScript compiler as a Node.js package

npm install -g typescript

# Then compile a typescript file

tsc helloworld.ts

Add the tsconfig.json file

The presence of a tsconfig.json file in a directory indicates that the directory is the root of a TypeScript project. The tsconfig.json file specifies the root files and the compiler options required to compile the project.

# create a default tsconfig.json file

tsc --init

A sample tsconfig.json file for Visual Studio Code can be,

{

"compilerOptions": {

"target": "es5",

"module": "commonjs",

"sourceMap": true

}

}

Transpile TypeScript into JavaScript in Visual Studio Code

Open the directory containing the tsconfig.json file in Visual Studio Code, and press Ctrl + Shift + B (i.e. Run Build Task) to either,

- build the project once, or

- make the TypeScript compiler watch for changes to the TypeScript files and runs the transpiler on each change.

To set a default behaviour when pressing Ctrl + Shift + B, select Configure Default Build Task from the global Terminal menu and set the default build task so that it is executed directly when you trigger Run Build Task (Ctrl + Shift + B).

Type inference in TypeScript

TypeScript supports type inference, for example,

var num = 2; // num has the type number

var num; // num has the type any, which is the base type for all types

But explicit type is recommended, so the above can be re-written as below:

var num: number = 2;

var num: number;

Defining the type

// for a variable

var a: number = 2;

Working with libraries written in JavaScript

A lot of the libraries, such as jQuery/Node.js/AngularJS etc., are written in plain JavaScript; they export varialbes and functions without type information. And it's too hard to re-write them in TypeScript.

When your TypeScript file needs to use these libraries, you can use an ambient declaration file for that third party library. An ambient declaration file by convention is stored in a .d.ts file, and it contains ambient declarations that describe the types that would have been there, had the third party library been written in TypeScript.

Your TypeScript file that uses these ambient declaration files will then be compiled into plain JavaScript using the variable/functions provided by the third party library.

The DefinitelyTyped repository contains a lot of high quality TypeScript defintions for some popular JavaScript libraries.

An example using ambient declaration in a TypeScript file is as below,

/** Example ambient declaration*/

// Reference the types file

/// <reference path="knockout-2.2.d.ts">

declare var ko: KnockoutStatic; // meaning the variable ko is not in this file, but it's coming from somewhere else, in this case, the Knockout typings file

var name = ko.observable('Zean'); // you get intellisense here

The above TypeScript file will then be compiled into a plain JavaScript file using the ko defined in the Knockout library.

Common types in TypeScript

Primative types

The commonly seen primative types in TypeScript are number, boolean, string, string [].

The any type

A type, in general, is a constraint on a value. The any type is the base type of all types in TypeScript, and it essentially places no constraint on a value.

A variable of any type can be defined as,

var data: any;

var data; // when there's is no type annotation, the `any` type will be inferred.

Object types

There are a few ways to specify the type of an object variable

// Object

var o1: Object;

o1 = {x:1}

o1.x // no intellisense

// {}

var o2: {};

o2 = {x:1}

o2.x // no intellisense

// {x: number}

var o3: {x: number};

o3 = {x:1}

o3.x // intellisense

// {x: number}

var o4 = {x: 1}

o4.x // intellisense

Type of functions

The type of a function describes the types of all its input variables and its return type. For example, the function

var foo = function (x: number) { return number; }

has the type

(x: number) => number

There are a few ways to specify the function type of a function variable,

// Function

var f1: Function;

f1 = function(x: number) { return x; }

// (x: number) => number

var f2 : (x: number) => number

f2 = function(x: number) { return x; }

// (x: number) => number

var f3 = function(x: number) { return x; }

A more complex example can be,

// (x: {w: number, h?:number | undefined}) => number

var f4 = function(x: {w: number, h?: number}) { return x.w * x.w; }

// it can be simplified as below using lambda syntax

// (x: {w: number, h?:number | undefined}) => number

var f4 = (x: {w: number, h?:number}) => x.w * x.w

Interfaces in TypeScript

An interface describes the minimum number of fields/properties/functions and the type of each field/property/function that an implementing object has to have.

JavaScript has no concept of interfaces. That means, the interfaces will not be compiled into anything in JavaScript, and the JavaScript rumtime will have no mention of interfaces anywhere.

1. Interface Examples

Example A

We can simplify this,

var p: {

firstName: string,

lastName: string,

address?: string,

getFullName: (firstName: string, lastName: string) => string

}

p = {

firstName: 'Zean',

lastName: 'Qin',

getFullName : (firstName, lastName) => firstName + ' ' + lastName

}

to the following

interface Person {

firstName: string,

lastName: string,

address?: string,

getFullName: (firstName: string, lastName: string) => string

}

var p: Person;

p = {

firstName: 'Zean',

lastName: 'Qin',

getFullName : (firstName, lastName) => firstName + ' ' + lastName

}

Example B

interface Person {

getFullName: (firstName: string, lastName: string) => string

}

function getPerson(): Person {

var innerVale: number = 2

var getFullName = (firstName: string, lastName: string) => firstName + ' ' + lastName + innerVale

return {

getFullName: getFullName

}

}

var p = getPerson();

p.getFullName('Zean', 'Qin');

Another example interface,

interface IEngine {

// fields

model: string; // field that an implementing class must have

year?: string; // optional field that an implementing class can have

// functions

start(callback: (startStatus: string, engineType: string) => void): void;

stop: (callback: (stopStatus: boolean, engineType: string) => void) => void;

}

A class implementing this interface can be,

class Engine implements IEngine {

model: string;

year?: string;

constructor(model: string, year: string) {

this.model = model;

this.year = year;

}

start(callback: (startStatus: boolean, engineType: string) => void): void

{

// implemnetation details

// ...

}

stop(callback: (stopStatus: boolean, engineType: string) => void): void {

// implementation details

// ...

}

}

And a class depending on this interface can be,

class Auto {

engine: IEngine;

constructor(engine: IEngine)

{

this.engine = engine;

}

}

2. Extending an interface

interface IPerson {

name: string;

address?: string;

}

interface Student extends IPerson {

studentId: string;

}

Classes in TypeScript

Class structure

A class in TypeScript is a re-usable container that encapsulate code, such as functions and variables. The main members of a class are,

- fields i.e. variables for storing the state,

- constructors for initialising the fields,

- properties i.e. ways to get/set field values (they act as filters), and

- functions.

A couple of sample classes are,

class Engine {

// the `public` keyword automatically generates a public field with the same name and type.

constructor(public hoursePower: number, public engineType: string) {}

}

class Car {

// fields

// by convention, the name of a private field starts with _

// the ! is to stop a warning from the tsc, see https://github.com/Microsoft/TypeScript-Vue-Starter/issues/36#issuecomment-371434263

private _engine!: Engine;

// constructor

constructor(engine: Engine)

{

this.engine = engine;

}

// properties

get engine() : Engine {

return this._engine;

}

set engine(value: Engine)

{

if(value == undefined) throw 'Please supply an engine.';

this._engine = value;

}

// functions

start(): void { // no need to use the key word `function` when inside a class

alert('Car engine started .');

}

}

and the Car class can be used as,

var engine: Engine = new Engine(1, 'v8');

var car: Car = new Car(engine);

console.log(car.engine.engineType);

You can cast objects from one type to another in TypeScript using

var newObj = <NewType> oldObj;

Extending a class

class ChildClass extends ParentClass {

constructor() {

// must call base class constructor with the needed parameters.

super();

// initialise child class fields here

...

}

}

Modules

Similar to the fact that a class is a container for fields/properties/functions, a module is a container for classes/interfaces/variables/functions.

1. Declaring/extending a module

// Declaring a module explicityly

module dataservice {

// code

}

If you create classes, variables or functions but not wrap them inside a module, you will create an internal module that gets added and extended to the Global Namespace. For exameple,

// Declaring a module implicityly

// Both the class A and the variable t are in the global module namespace.

class A implements IInterface {

// code ...

}

var t = new A();

The

namespace(ormodule) keyword declares a new module or extends (i.e. adding members) to an existing module with the same name. Modules and files no direct relationship (or a many to many relationship if you have to); a module can span through multiple files and a file can contain multiple modules. For example, in the same TypeScript file, you can have,

namespace Shapes {

export class Rectangle {

constructor(public width: number, public height: number) {}

}

}

namespace Shapes {

export class Circle {

constructor(public radius: number) {}

}

}

var rect = new Shapes.Rectangle(1, 1);

var circle = new Shapes.Circle(2);

2. Internal module accessibilities

By default, all members of a module can only be accessed internally i.e. within the module, use the export keyword to make a member publicly accessible outside of the module. e.g.

namespace Shapes {

export class Rectangle {

constructor(public width: number, public height: number) {}

}

}

// adds the rect to the global name space, or

var rect = new Shapes.Rectangle(1, 1);

// create another module to avoid global scope pollution. i.e. by adding the `myprogram` module to the global module.

namespace myprogram {

function run() {

var rect = new Shapes.Rectangle(1, 1);

}

run(); // invokes the function

}

Immediately-Invoked Function Expression or IIFE, pronounced "iffy", is a function that runs immediately after it's being defined. It's done by writing a function definition followed by (). For example,

(function() { console.log("Zean Qin"); })()

The outer () disambiguates function expression from statements, and locks in values and saves state. It's used to remove its wrapped members from the global scope to avoid global scope pollution and creates privacy.

Modules created in TypeScript are converted into IIFE in JavaScript.

A more complex example,

namespace App.Tools.Utils {

export class A {}

}

namespace App.Tools.Shapes {

export class Rectangle {}

}

namespace App.Tools.Shapes {

export class Circle {}

}

namespace MyProgram {

import Utils = App.Tools.Utils;

import Shapes = App.Tools.Shapes;

function run() {

var util = new Utils.A();

var rect = new Shapes.Rectangle();

var circle = new Shapes.Circle();

}

run();

}

If these modules are defined in separate .ts files, we need to include /// <reference path="...." /> to tell the compiler to merge in the modules defined in those files.

Note: the

/// <reference path="...." />is ONLY to tell the editor where to find a dependency to the intellisense will work at design time, we still need to make sure we load those dependencies first at runtime e.g. include those.jsfiles first in an html file.

3. External modules

Sequencing scripts and dependencies in those scripts are really really difficult especially in large applications.

External modules are separately loadable modules i.e. we can load them separate from each other only as needed.

AMD

Asynchronous Module Definition (AMD) loads files and modules asynchronously as you need them, and the developer just needs to define upfront which modules depend on which and it will load them in the proper sequence. require.js is a great library that helps us manage dependencies.

In auto.ts, we have

export interface IAuto {}

export class Auto implements IAuto {}

then, in main.ts, we can have

import auto = require("./auto.ts")

var a = new auto.Auto();